Photo Credit: Sacha Chua

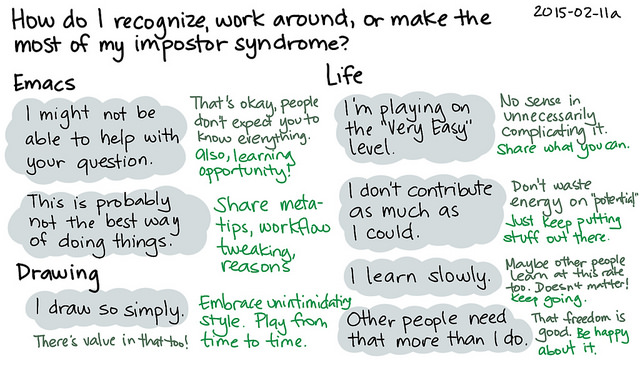

Photo Credit: Sacha Chua Have you ever felt like you didn’t really earn something you achieved? Have you worried from time to time that you’re not as smart or capable as others think you are? If so, you may have experienced what psychologists refer to as impostor syndrome. In today’s post, I’ll review what impostor syndrome is, factors that contribute to it, and ways that psychologists have found of coping with it.

What is impostor syndrome? Impostor syndrome refers to feeling that one is not intelligent or talented, despite there being objective evidence that one is successful or accomplished. People who experience impostor syndrome may attribute their success to external factors, such as luck. They believe that others overestimate their capabilities, and fear being “exposed” as someone who is lacking in talent. Individuals with impostor syndrome often downplay their successes, and have difficulty enjoying their accomplishments.

One of the psychologists who pioneered research on impostor syndrome, Pauline Rose Clance, said that she herself experienced feelings of impostor syndrome in graduate school: “I would take an important examination and be very afraid that I had failed.” A college professor with impostor syndrome claimed “some mistake was made” when she was hired for her job. Another woman said of her job, “Obviously I’m in this position because my abilities have been overestimated.”

How is impostor syndrome measured? Impostor syndrome is often measured with a self-report questionnaire, the Clance Impostor Phenomenon Scale. If you’re interested in finding out whether you may be experiencing impostor syndrome, you can take this short quiz here.

How does impostor syndrome relate to well-being? Impostor syndrome is not an official diagnosis in the Diagnosic and Statistical Manual (psychologists’ handbook for categorizing different types of mental health conditions), but it can occur along with anxiety and depression. Research has found that impostor syndrome is associated with low self-esteem, neuroticism, and poorer mental health. Why might this be the case? People with impostor syndrome are often prone to perfectionism: they worry about small details on work projects and, when they succeed, they assume that their success was only possible due to this level of perfectionism. Because people attribute their success to luck or to the fact that they worked so hard (rather than as being due to their ability), impostor syndrome makes it harder for people to celebrate and take credit for their successes. As a result, impostor syndrome has a self-perpetuating quality: even experiencing significant success doesn’t raise self-views for people who have impostor syndrome.

Who is at risk for developing impostor syndrome? Impostor syndrome can affect individuals in a wide variety of professions. While many psychologists have studied the phenomenon in college students, it can affect individuals in fields as diverse as law, medicine, and teaching. And although the theory was originally developed to explain the self-doubts of successful women, newer research has found that both women and men can experience impostor syndrome. Some research has also found that being a member of an ethnic minority group or being LGBT is associated with an increased likelihood of experiencing impostor syndrome. Pauline Rose Clance and her colleagues have suggested that being a member of a stereotyped group can cause someone to feel self-doubts when they experience success and, thus, contribute to experiencing impostor phenomenon.

Researchers have also suggested that certain family environments may contribute to impostor syndrome. In their research on over 150 women with impostor syndrome, Pauline Rose Clance and Suzanne Imes found that women with impostor syndrome often experienced one of two different types of family environments as children. In some cases, the women were told as children that they were incredibly smart and gifted, and that they should be able to achieve great things without much difficulty. As a result, when the women did experience difficulties with their work, they concluded that they must not be smart. In other cases, the women recalled that another child in the family was labeled as intelligent, which led to lingering self-doubts about their own intelligence. (While this original study looked at women, it’s important to note that imposter syndrome can develop in men as well.)

Other research has suggested that certain types of parenting styles can contribute to impostor syndrome. In one study, individuals with impostor syndrome reported that their parents had been overprotective and less caring (compared to the parents of individuals who did not have impostor syndrome).

Finally, it’s important to note that impostor syndrome is especially likely to occur when starting something new (for example, starting a new academic program or job). People who have achieved a significant accomplishment may have trouble internalizing this success and thus experience impostor syndrome.

What can you do if you think you might have impostor syndrome? If you think you might be experiencing some of the symptoms of impostor syndrome, there are many steps you can take to cope with these feelings:

- Identify automatic thoughts: People with impostor syndrome have a variety of automatic thoughts: subconscious thought patterns that contribute to their behavior (e.g. thinking, “I’m not qualified” in a situation related to achievement). Becoming aware of, recognizing, and addressing these thoughts can be helpful. If you’re interested in learning more about automatic thoughts and how they are addressed through cognitive behavioral therapy, click here to read more.

- Get support from others: Clance and Imes found that talking to others who were experiencing impostor syndrome was especially beneficial. Learning that other people share the same doubts as you can be reassuring. Additionally, seeing someone else who is successful yet still harbors self-doubts can help you to realize that these self-doubts aren’t rooted in reality.

- Focus on your strengths: Give yourself time to take stock of your abilities and concentrate on what you know you do well. For example, remind yourself of your successes or mentor others who can benefit from your expertise. And when you succeed, take time to celebrate your successes!

- Cultivate a growth mindset: The psychologist Carol Dweck has found that certain mindsets can help us to cope better with failure. Some people have a fixed mindset (the idea that our intelligence and abilities remain unchanged over time) while others have a growth mindset (the idea that we can constantly work to increase our abilities). So if you find yourself worrying about the possibility of failing at a task, consider reframing it: instead of worrying about failure as revealing a lack of ability, try to see failures as an opportunity to grow and learn.

Imposter syndrome isn’t uncommon at all, but because people tend not to admit that they feel like a fraud, it can be quite isolating to experience imposter syndrome. However, by reaching out to others and addressing the thoughts and behaviors that contribute to impostor feelings, you can begin to give yourself credit for the successes you’ve earned.

Further Reading:

Caltech Counseling Center: The impostor syndrome

Pauline Rose Clance: Impostor syndrome

Kirsten Weir: Feel like a fraud?

About this Contributor: Elizabeth Hopper is a PhD candidate in Social Psychology at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Prior to attending UCSB, she received her BA in Psychology and Peace & Conflict Studies from UC Berkeley and worked in a research lab at UC San Francisco studying health psychology. Her research interests include positive emotions, close relationships, coping, and health. Outside of the research lab, Elizabeth can often be found going to yoga class, teaching her puppy new tricks, and working on her creative writing.

Leave a reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Clark Rector, M.A. said on March 7, 2015

I haven’t followed all the links yet…but I wonder if self-labeling one’s self as an imposter could also be a psychological defense against something: perhaps the fear of defeating another person and fearing retaliation, or the fear of failure/not measuring up to one’s own standards, or for some the anxiety elicited when others may be envious of your accomplishment.

Building on the finding that LGBT may experience this more, I suspect that in-group or out-group status may be key factors. And I would suspect that the imposter feelings would be even more intense or complicated if the person was ambivalent about group inclusion.

A alternative explanation to the dissonant feelings around the imposter phenomenon is that just because a person, say, lands a job that is generally considered “successful” in one’s culture, that does not mean that it’s a job that the individual truly feels is successful to them on a deep level. This may create a state of cognitive dissonance in which the cultural value of “success” does not match with the individual’s true experience of “success.”