Buddhist Psychology – Understanding the Root Causes of Suffering

Introduction

Qualities Leading to Unhealthy Psychological States

Qualities Leading Healthy Psychological States

Buddhist Psychology Tools

Some consider the Buddha, who lived 2,500 years ago, to have been the first psychologist to walk the planet. While many think of Buddhism as primarily a religion, it is also a form of psychology that is consistent with the scientific method that stresses observation and judging for oneself (versus simply following dogma). It has several formal applications in the therapy field today, the more known ones being “Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction” (MBSR) and “Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy” – a blend of Buddhist philosophy and cognitive therapy.

Buddhist Psychology theory believes our psychological state depends not so much on our particular circumstances, but more on how we relate to what life brings our way. It acknowledges that pain – whether physical or emotional – is an unavoidable part of life and with that pain comes some suffering. However, as human beings we tend to add additional layers of psychological suffering by how we engage with our experiences. In particular, it’s a strong desire to control things – to hang on to what we want and push away what’s unpleasant – that gets us into trouble.

According to Buddhist philosophy, when we cultivate certain ways of being in the world, then we’re more or less apt to experience the qualities associated with mental health – things like insight, balance, joy and kindness. Below is a discussion of the core factors that lead to both unhealthy and healthy states of mind. There are many types of mindfulness practices and tools designed to foster healthy mental states and work effectively with the unhealthy ones, some of which are referenced below as well.

Mindfulness 101: for those who aren’t familiar with the concept of ‘mindfulness’ from the Buddhist perspective, its central premise is about paying attention to the present moment with a sense of receptivity, non-judgment and compassion toward whatever is arising. Contrary to popular belief, it’s not about throwing out all cares and simply “living for the moment.” Nor, is it a recipe for passivity. Rather, mindfulness is about connecting fully with the here and now, recognizing there is of course a past and a future, but not fixating on either one of those. While it’s healthy to understand the past and plan for the future, it’s easy for the mind to get caught up in those mental states to one’s own detriment.

When practiced and applied, the mind becomes more open, clear and less reactive, creating more space to make choices – choices about things like what perspectives to feed and what actions to take (or not take). In other words, mindfulness can help us lead wiser and more fulfilling lives. For a more in-depth discussion on the Buddhist practice of mindfulness, go here: What is Mindfulness?

Buddhist Psychology – Unhealthy Psychological States

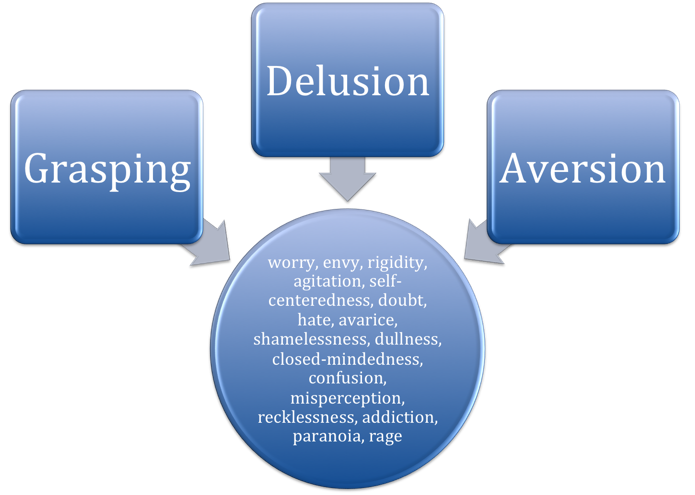

From the perspective of Buddhist Psychology, emotional and behavioral difficulties have their roots in three (3) primary areas known as Grasping, Aversion and Delusion. These terms are often used interchangeably with ‘Greed’ (grasping), ‘Hatred’ (aversion) and ‘Ignorance’ (Delusion).

As Buddhist teacher and psychologist Jack Kornfield writes in The Wise Heart: A Guide to the Universal Teachings of Buddhist Psychology (p.54), the psychological states of “Grasping, aversion, delusion give rise to: worry, envy, rigidity, agitation, self-centeredness, doubt, hate, avarice, shamelessness, dullness, closed-mindedness, confusion, misperception, recklessness and others.”

Let’s take a closer look at what these terms mean:

1.) What is Grasping? Hanging on too tight to what’s there.

Example: you’ve just had a great weekend and now you don’t want it to end. As the clock ticks toward midnight on Sunday, you continue to resist, thinking “I don’t want to go to work tomorrow.” Anxiety and frustration build. That’s a simple example of grasping — not wanting the weekend (what’s ‘pleasant’ at the time) to end.

Other examples of grasping include: feeling overly attached to something, including how it might turn out / the outcome; wanting to always be in control; the inability to let go; insatiable desire; never feeling like you have enough (e.g., food, money, attention, approval, etc.); any type of addiction; greed. Part of being human is desiring things – that’s normal. But, as some Buddhist teachers have said, the problem is that far too often we desire ‘too little’ — in the sense that we have a narrow view of things that we think will make us happy. Alternatively, if we could have an attitude of acceptance for whatever life brings our way, for when we ‘succeed’ and ‘fail’, for when we get what we want and don’t, then we’re more apt to find an inner peace and deeper joy that’s not dependent on how things go on the external level.

2.) What is Aversion? Mentally pushing things away.

Example: you know that exercising is good for your health, but you don’t feel like exerting the effort it takes to go to the gym. That’s a simple example of aversion. Any type of procrastination or avoidance involves aversion.

Other examples of aversion including: wanting things to be different than they are; avoiding emotional pain that’s a normal part of living (e.g., grief, embarrassment, fear); self-judgment; judgment of others. At its most extreme, ‘aversion’ takes the form of hatred, discrimination and aggression toward others or oneself.

3.) What is Delusion? Ignorance – not seeing things for what they truly are, especially oneself.

Example: believing that your self-worth is based on things like title, status or looks, as defined by mainstream culture. Judging yourself as fundamentally better or worse than other people is another example of deluded thinking (note, this is different from discerning different skill levels people may have in certain areas).

‘Delusion’ from the Buddhist perspective is a bit different than how it’s used in clinical psychology – where it’s described in more severe terms (e.g., a man believing he’s pregnant; a person believing they have powers like a comic book superhero). In Buddhist Psychology, delusion refers to things like: confusion about and estrangement from who we really are as human beings (e.g., spiritual beings in a physical body); identifying strongly with outer aspects of self that’s related to ego, rather than recognizing the deeper, true self; seeing oneself as separate from others, instead of recognizing the interconnection to all life. Taking things personally is a common example of delusion or ignorance, from the Buddhist Psychology perspective.

When we’re in the throes of grasping, aversion and delusion, we suffer more psychologically. Now let’s take a look at the factors that lead to healthy psychological states.

Buddhist Psychology – Healthy Psychological States

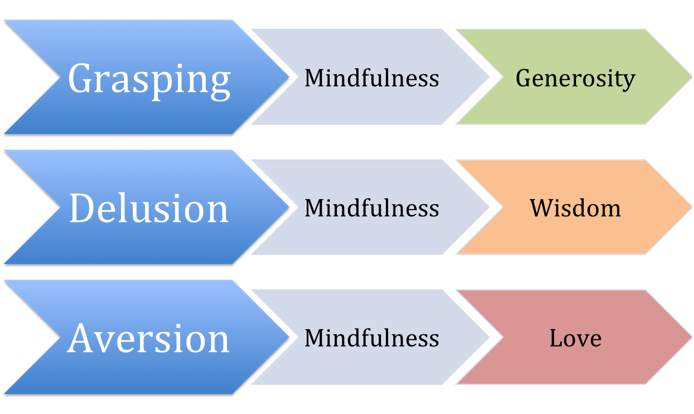

In contrast to grasping, aversion and delusion, the “Healthy States of Wisdom, Love and Generosity give rise to: mindfulness, confidence, graciousness, modesty, joy, insight, flexibility, clarity, equanimity, adaptability, kindness and others.” (Jack Kornfield, The Wise Heart, p. 54).

Generosity, wisdom and love are hallmarks of what it means to be mentally healthy and as described above, lead to a variety of other positive mental sub-states.

Let’s take a closer look at what these terms mean from the perspective of Buddhist Psychology:

1.) Generosity: the antidote to Grasping and Clinging.

Like most spiritual traditions (at least in theory), generosity is a core value. Buddhists use the Pali term Dana to refer to the act of giving from the heart – that is, giving without expectation of something in return. Generosity simply feels good, but it can also be particularly moving when we’re stuck in the throes of wanting or grasping (i.e., in a trance of scarcity or disconnection).

As meditation teacher Phillip Moffitt writes: “Dana means practicing generous behavior in all aspects of your life, not just giving money or sharing material possessions. Certainly the emotional impulse to practice dana most easily arises when you participate in providing sustainability for others, whether it is shelter, food, clothes, or medicine. But with less immediate life needs, such as education, safety, or earning a living, the appropriate dana may be the gift of your time. When it comes to intangibles such as justice and dignity, what may be most appropriate is to voice your support. Dana, along with compassion, is a cornerstone of mindful social activism.” Read Phillip’s entire excellent article on Dana here: The Gift of Generosity.

2.) Wisdom: the antidote to Delusion or Ignorance.

From the Buddhist perspective, wisdom (or insight) is cultivated through mindfulness practice — paying attention to the present moment with a sense of openness, non-judgment and compassion for whatever is arising. You can practice mindfulness formally, like through meditation, or more informally when partaking in virtually any other activities. Generally speaking, an attitude of curiosity and inquiry, rather than presumption or closed-mindedness, leads to wisdom.

With mindfulness, we are able to gain perspective that is often otherwise obscured through a process known as ‘identification‘ – where we’re so immersed in our experience that we feel it is us, in contrast to seeing it for what it is – an experience. Life is always changing, whether in small or big ways. Wisdom is about recognizing this fluidity, rather than grasping onto it as one’s identity, as who we are. Another key aspect of wisdom from the Buddhist perspective is recognizing the interconnectedness of life, rather than seeing ourselves as independent entities. This sense of separateness, so rampant in modern society, is responsible for much of the psychological suffering seen throughout the world today.

3.) Love: the antidote to Aversion and Hatred.

Love can take many forms. Caring, compassion, friendliness, goodwill, warmth, and showing interest in another’s life are but a few examples. At anytime, we can choose to foster an attitude of love and compassion toward oneself and others.

Buddhists recognize the holiness in all human beings. When we sense this divinity, it’s easy to feel love. When we don’t easily see the beauty, goodness and wholeness in another person, it simply means that it’s become obscured by conditioning – either theirs or our own. Accordingly, when we naturally feel love — either an inkling or a surge — use that as an opportunity to expand those positive feelings even further and know that you’re giving yourself a positive mental health infusion in the process. The meditation practice of lovingkindness, or Metta, is one excellent way to cultivate more love and compassion toward oneself and others. Try it out here: UCLA Mindful Awareness – Lovingkindness Meditation (9 minute guided meditation).

Forgiveness practices can also be particularly helpful with regards to letting go of aversion and hatred. It’s important to remember not to try to “force” yourself to feel a certain way toward somebody. For instance, it can be very hard to conjure up feelings of compassion toward somebody that has caused much hurt. During these times, you may want to take your attention off the hurtful person and direct your sense of love toward somebody that evokes that feeling more easily.

In summary, the good news is that we can work at both cultivating the healthy states and unraveling the unhealthy ones. As Jack writes, “When healthy factors are present, unhealthy ones are not. So, when we foster healthy states, unhealthy ones disappear.” (The Wise Heart, p. 56). So, again, when we feel the slightest bit of love or generosity toward another, that marks a great opportunity to deepen into that state. Alternatively, when we’re gripped in aversion, that’s a great time to try to cultivate wisdom and acceptance. And, when we’re feeling particularly desirous of something, instead of feeding that wanting mind, try to flip it by doing something generous for another person.

Buddhist Psychology Tools

Below you can learn about more about mindfulness practices, including detailed and practical exercises to help untangle the unhealthy states and foster the healthy ones.

The R-A-I-N Tool

Gratitude Practices

What is Mindfulness?

Free Guided Meditations

Anger Management: Internalize Sacred Figure Exercise

What is Mindfulness-Based Psychotherapy? By Tom Pedulla, LICSW

Guided Lovingkindness (Metta) Exercise (27 minutes)

Leave a reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Clark Rector, M.A. said on March 30, 2015

I love this page! Buddhist psychology has been so helpful personally and professionally. It is a peaceful way of living, and helps me from getting all attached (same as grasping, I believe?) to certain outcomes. And for me, practicing mindfulness is something to return to again and again and again, to enter into an improved state of mind in which I can accept what is occurring rather than fighting against it. I’m curious to know if others have found Buddhist psychology to be helpful.